It was Cecil Edwin Webber who first came up with the idea of miniaturising the Doctor and his companions as a potential story idea. 'Bunny' Webber (will we ever find out why his friends called him that?) had been commissioned by Head of Drama Sydney Newman, newly arrived from ITV franchise ABC, to develop a new Saturday tea time adventure series from a recent BBC report into the science fiction genre.

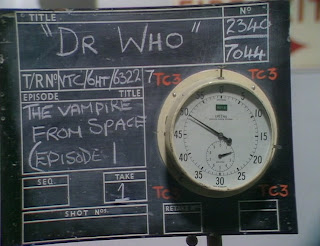

Early in 1962, Head of Serials Donald Wilson had asked Alice Frick and Donald Bull, of the BBC Survey Group, to provide an overview of the genre, its potential and the kind of audiences it might attract. A follow up report was duly presented on 25 July 1962 by Frick and writer John Braybon that outlined the kind of stories and concepts that could be developed as a science fiction series. In March 1963, Webber and Wilson then developed an outline for a drama called The Troubleshooters but this was abandoned after further brainstorming between them and Newman was consolidated into a document, drafted in May 1963, called 'Dr. Who - General Notes on Background and Approach'.

This document essentially devised the format, structure and characters of the series that would eventually become Doctor Who. It was here that Webber first postulated the kinds of stories the fledgling series concept might tell: 'The first two stories will be on the short side, four episodes each, and will not deal with time travel. The first may result from the use of a micro-reducer in the machine which makes our characters all become tiny.' (1) Oddly enough, he also suggested 'Was Merlin Dr. Who? Was Cinderella's Godmother Dr. Who's wife chasing him through time?' Funny how the series would eventually return to what Newman thought were rather fanciful ideas.

Rex Tucker, whom Newman had hired as an interim producer for the proposed Doctor Who series and who had a great deal of input into its development, understood Newman's thinking and had already sent a memo to Wilson stressing that, in his opinion, Lime Grove Studio D was not fit for purpose for the technical requirements of Doctor Who. Tucker had already made initial contact with composer Tristram Cary with a view to producing the series' theme, been involved in early casting and was lined up to direct the first serial, planned as Webber's story.

He rejected the draft scripts of 'The Giants' after Webber had attempted to refine them and asked Coburn to rewrite An Unearthly Child with a view to replacing Webber's story. Tucker's rejection of them was certainly because of the technical problems that would face the production in Lime Grove D and studio allocation would be a continuing thorn in the side of the series' production throughout 1963 and 1964.

Early in 1962, Head of Serials Donald Wilson had asked Alice Frick and Donald Bull, of the BBC Survey Group, to provide an overview of the genre, its potential and the kind of audiences it might attract. A follow up report was duly presented on 25 July 1962 by Frick and writer John Braybon that outlined the kind of stories and concepts that could be developed as a science fiction series. In March 1963, Webber and Wilson then developed an outline for a drama called The Troubleshooters but this was abandoned after further brainstorming between them and Newman was consolidated into a document, drafted in May 1963, called 'Dr. Who - General Notes on Background and Approach'.

This document essentially devised the format, structure and characters of the series that would eventually become Doctor Who. It was here that Webber first postulated the kinds of stories the fledgling series concept might tell: 'The first two stories will be on the short side, four episodes each, and will not deal with time travel. The first may result from the use of a micro-reducer in the machine which makes our characters all become tiny.' (1) Oddly enough, he also suggested 'Was Merlin Dr. Who? Was Cinderella's Godmother Dr. Who's wife chasing him through time?' Funny how the series would eventually return to what Newman thought were rather fanciful ideas.

'hardly practicable for live television'Webber developed the idea into a storyline 'The Giants' which was intended as the very first serial to launch the series. It contained elements that would eventually be transferred to Anthony Coburn's An Unearthly Child (also variously titled The Tribe of Gum and 100, 000 BC), then intended as the second serial, after his proposed synopsis was received with some reservations by Newman and then returned to Donald Wilson on the 7 June 1963. Newman was not altogether happy with the four episode breakdown and noted it was 'thin on incident and character'. He also felt that the scale of Webber's ambition, the use of large scale sets and visual effects and of the reduced-in-size Doctor and his companions encountering spiders, was 'hardly practicable for live television'. (2)

Rex Tucker, whom Newman had hired as an interim producer for the proposed Doctor Who series and who had a great deal of input into its development, understood Newman's thinking and had already sent a memo to Wilson stressing that, in his opinion, Lime Grove Studio D was not fit for purpose for the technical requirements of Doctor Who. Tucker had already made initial contact with composer Tristram Cary with a view to producing the series' theme, been involved in early casting and was lined up to direct the first serial, planned as Webber's story.

He rejected the draft scripts of 'The Giants' after Webber had attempted to refine them and asked Coburn to rewrite An Unearthly Child with a view to replacing Webber's story. Tucker's rejection of them was certainly because of the technical problems that would face the production in Lime Grove D and studio allocation would be a continuing thorn in the side of the series' production throughout 1963 and 1964.

Although 'The Giants' was rejected and Webber was paid a staff contribution fee of £187.10s.0d. for the two scripts he wrote, script-editor David Whitaker still saw mileage in the concept and attempted to schedule a similar story into the first season of Doctor Who. On the 8 August, he had asked Ayton Whitaker, the Drama Group Administrator at the BBC, about the need to mount such a story in studios other than Lime Grove: 'I am very loathe to abandon the idea of a 'minuscule' adventure for Doctor Whowithout asking you what chances there are of eventual transfer from D to a studio capable of handling the visual effects which are, after all, an integral part of this project.' (3) A memo from Donald Wilson to Newman suggested a desire to produce 'the "miniature" adventure of Dr. Who' as the fourth story of the first season and requested Newman to 'support an application for TC3, TC4 or Riverside 1' as the studio in which to make it.

Whitaker commissioned Robert Gould to develop the scripts in September 1963 but by 4 February 1964, Gould's work on the now titled The Minuscules was proving problematic and Whitaker requested that he abandon the scripts. On 23 March, Whitaker commissioned Louis Marks to provide a new 'minuscules' storyline and by May he had been formally contracted for the four scripts of Planet of Giants. Marks had found inspiration in the recent publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring. Her investigation into the effects, particularly on the food chain, of chemical pollution and the over-use of insecticides such as DDT had 'caused a considerable stir' and 'as miles of fields and farmlands disappeared beneath motorways, housing estates and tower blocks, people were beginning to question the post-war emphasis on economic growth and scientific progress'. (4)

Not only was Marks reflecting the concerns raised by Carson's book but he was also following in a tradition of 'resizing' in popular fiction and culture - everything from Carroll's Alice in Wonderland and Mary Norton's The Borrowers to the B movie machinations of Dr. Cyclops (1940) and Richard Matheson's sublime The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). The 'Tales of Scotland Yard' aspect of the story also resembles the 50 minute 'bobby on the beat' drama Dixon of Dock Green, one of the BBC's most successful long running dramas and, at the time, grabbing 13 million viewers on a Saturday night. Tat Wood and Lawrence Miles explain how this format was already looking anachronistic within a series such as Doctor Who and during a period when 'the grammar of television accelerated' and a production such as Z Cars was already ringing the changes where it had 'been estimated that the average length of a shot in an episode... was twelve seconds.' As they suggest, 'That's almost subliminal by 1962 standards'. (5)

It is therefore not surprising that the man handling the complexities on this serial was Associate Producer Mervyn Pinfield, a former member of the Langham Group, a short lived 'experimental television group' led by Anthony Pelissier which attempted to develop the aesthetics of television and move it away from its theatrical origins. It was an R&D opportunity for Pinfield to work on inlay, overlay and split-screen techniques and several groundbreaking dramas, including Torrents of Spring (tx 21/05/1959), had been made by the group. Many of these techniques filtered into the likes of Z Cars and Doctor Who. At the suggestion of Pinfield, Verity Lambert and Bernard Lodge had watched the 'howl-around' footage that a technician called Ben Palmer created for Amahl and the Night Visitors, a drama broadcast in 1951, when they were experimenting with similar effects for the opening titles of the series.

Pinfield was training other directors in such techniques and was the go-to-guy if a Doctor Who serial held a particular technical challenge. He directed all but one of the episodes of Planet of Giants with the fourth, 'The Urge to Live' handed over to Douglas Camfield. Camfield had been working on Doctor Who as film editor and production assistant, previously shooting and editing a number of sequences for An Unearthly Child and Marco Polo, and he would become one of the series' most prolific directors. In terms of television pacing, Camfield's work on the fourth episode of the serial, then called 'The Urge to Live', and his requirement to edit together this and the third episode 'Crisis' is also an indication of how much faster television would become as directors became confident with new production techniques.

Whitaker and producer Verity Lambert had also managed to get the production moved to Television Centre and on 21 August recording took place for the first episode in TC4 after visual effects inserts had been filmed at Ealing between 23 and 30 July. The following three episodes were recorded on each Friday between 28 August and 11 September. Sound mixer Alan Fogg 'pre-recorded several segments of specially speeded up or slowed down soundtrack to show how, comparatively, a tiny voice sounds to a giant, and vice versa'. (6)

The move to TC4 enabled designer Ray Cusick to manage the technical challenges of creating giant sized props such as matchboxes, earthworms and ants in Farrow's garden and, later, his standout work recreating a briefcase, the sink and its plughole. The serial also had to deal with 'precisely lined-up inlay shots, half-silvered mirror shots, glass shots and back-projections to overcome the great hurdle of having the travellers and the 'giants' in the same shot'. (7)

Cusick created the first ever glass shot for the series to extend the ground floor of the house and the production used front projection techniques to show the TARDIS crew interacting with Farrow's body, a rack of test tubes and a telephone. He allegedly also came up with the idea of using the gas-jet to attack Forester. It's worth noting that these over sized props, sets and effects were achieved on a shoestring budget well before Irwin Allen threw a ton of cash (a reported $250,000 per episode) at his Land of the Giants television series when it started shooting in Autumn of 1967.

Donald Wilson would have preferred leading off the second season of Doctor Who with The Dalek Invasion of Earth but the departure of Carole Ann Ford at the end of that story made it impossible to swap the two serials around. He was also of the opinion that Planet of Giants would benefit from editing. In a memo to Sydney Newman on 19 October, he noted: 'I am arranging to reduce the four-part serial entitled Planet of Giants to three parts. This is the'minuscule' story with which we must begin our new season and I am not satisfied that it will get us off to the great start that we must have if it runs to its full length. Much of it is fascinating and exciting but by its nature and the resources needed we could not do everything we wanted to do to make it wholly satisfactory'. (8) The last two episodes were transferred to 35mm film and Camfield edited them into one episode 'Crisis'.

The story is atypical for an Earth based adventure of the period in that its setting is contemporary and the threat is contained within the domestic environs of a house and garden. It's also commendable that it taps into environmental concerns, perhaps more relevant now than then, and Rachel Carson's widely credited influence on the environmental movement and widespread public concerns about pesticides in the face of industry disinformation and government's own failure in uncritically accepting industry claims.

Representing the disinformation and industry bluff are the 'villains' Farrow, Forester, Smithers and for DDT we have DN6. However, the dubious business practises of industry are only marginally explored and the editing of the third episode, while adding pace after two rather slow episodes, doesn't add any clarity to an already under-developed sub-plot. Farrow is played unremarkably and briefly by Frank Crawshaw but Alan Tilvern as Forester, is rather sinister and oily. There is some confusion over his motivation - he apparently developed DN6 but doesn't seem to have a clue who will manufacture and distribute it despite having killed Farrow and eventually gunning for Smithers too. The missing material from the original edits of 'Crisis' and 'The Urge to Live' briefly touches on this.

These conventions also include Bert and Hilda Rowse - the couple at the telephone exchange - who would have had the familiarity of characters from the likes of Dixon Of Dock Green and, indeed, the way the story turns from industrial espionage to village scandal does echo the weekly homilies dished out by George Dixon and company. Both characters feel like they've strayed out of an Ealing comedy and it is rather convenient for the story that Hilda, the exchange operator, is married to the local bobby. Even though the missing material does feature them it is understandable why Donald Wilson had it excised as it mainly revolves around Hilda's concerns about Farrow's phone being off the hook.

With three sets of characters - Forester and Smithers, Hilda and Bert, and the TARDIS crew - that rarely interact, Planet of the Giants does have its fair share of dull patches. The real joy of the story lies in the regular characters exploring their over-sized environment, beautifully realised despite the infancy of modern television production and technology, and how the characters, despite their size, go beyond simple exploration and seek to call attention to the harmful effects of the insecticide. Pinfield's direction offers up some little treats too. The slow pull back from the TARDIS, tucked away in the crazy paving of the garden, to a master shot of the garden and the house is a technically ambitious shot and his ability to match over sized props and actual props through zooming and editing works very well.

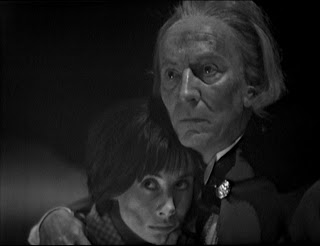

If there is a central figure worth watching this serial for then it has to be Jacqueline Hill as Barbara. Yes, you may end up berating Barbara for her singular failure to let her friends know that she has been infected by DN6 but Hill is rather brilliant at equally conveying the character's failure to do so. Her silent terror as she is frozen to the spot by the appearance of the giant fly is a stand out moment. The puppet effects for the fly are also, for their time, exceptional even if the prop was one borrowed from the Visual Effects Department and not created specifically for the production. Barbara does get turned into something of a shrinking violet (pun intended) on the one hand and someone who over-reacts on the other but Hill does manage to keep her fate compelling throughout.

She works well with Hartnell, whose performance has transformed the Doctor from the aggressive misanthrope of An Unearthly Child, and their domination tends to put Carole Ann Ford and William Russell into the shade. Ford rightly argues that her character wasn't written well and she's not wrong here. Russell is also written more or less as the brawny but resourceful school teacher hero figure and lacks development as a character.

After a season of stories where the Doctor has attempted to get Ian and Barbara back to Earth in 1963, he finally achieves it here and the pair of them, and the story, barely acknowledge this fact. Contemporary Earth settings will, of course, become a vital component of the series as it progresses into the later 1960s and into the 1970s and it is interesting to see how this is treated as almost a separate element in theDoctor Who format at this point.

What impresses most is, for the time, the stunning production design and visual effects from Ray Cusick. It really is a triumph of design that turns this exploration of a threatening domestic space into a realm of the uncanny. Here, the ordinary is made extraordinary - it's a World's Fair (as Ian at first rationalises it) of giant earthworms, ants and bees where evil and the unknown are embodied by drainpipes, sinks, plugholes, telephones, cats, matchboxes, seed packets and briefcases. Where else would the image of a man washing his hands in a sink create a terrifying cliffhanger to a drama?

(1) BBC Archive - The Genesis of Doctor Who

(2) Laurence Marcus, Television Heaven: The Origin of Doctor Who

(3) Howe, Stammers and Walker: The Doctor Who Handbook - The First Doctor

(4) Dominic Sandbrook: White Heat

(5) Tat Wood & Lawrence Miles, About Time 1963-1966

(6) Jeremy Bentham: Doctor Who - The Early Years

(7) Ibid

(8) Howe, Stammers and Walker: The Doctor Who Handbook - The First Doctor

Special features

Commentary

Moderated by Mark Ayres with vision mixer Clive Doig, special sounds creator Brian Hodgson, make-up supervisor Sonia Markham and floor assistant David Tilley.

Episode 3 and 4 Reconstruction (52:38)

Using the original scripts, newly recorded dialogue and animation, this feature gives viewers an idea of how the original four-part version might have appeared. On the positive side, the efforts of all involved must be applauded. The newly recorded audio matches are often incredibly good and combining these with existing footage and some modest pieces of animation produces a refined, more professional version of the kind of re-cons that fans have been making and watching for years. However, you can't create a silk purse out of a sow's ear in this instance and there's a very good reason why Donald Wilson decided to edit the two episodes into one.

The missing twenty five minutes are not the finest example of early Doctor Who and are perhaps rather atypical of even this period of the programme's output. There are many longueurs, particularly the exchanges between Forester and Smithers about disposing of Farrow and tampering with his report and the comedy Dock Green exploits of Hilda and Bert. As Carole Ann Ford correctly recalls, this is very dialogue heavy and that is emphasised by this reconstruction. The extension to the scene of the TARDIS crew mapping Farrow's notebook is a case in point. It just holds up the narrative for nearly a minute and a half. Many of the scenes involving Forester, Smithers, Hilda and Bert are simply repetitive. However, the poisoning of the cat, the Doctor's resolve to save the Earth and Barbara's emotional melt-down are good scenes and it's a pity they were consigned to the cutting room floor or were truncated. Some of the missing material does create some logistical problems in the existing edit of 'Crisis' but Wilson's decision seems, in retrospect, a wise one.

It's a laudable experiment, done for the right reasons and, while the material isn't the most engaging and we can understand why it never made it to the screen, this does perhaps create a viable template for potential re-cons on future DVD releases.

Rediscovering The Urge to Live (8:30)

Ian Levine explains the origins of Planet of Giants and how the concept was developed and finally realised. Also on hand are Carole Ann Ford and William Russell. Bill's entire memory of the show is 'a box of matches' and 'matches like telegraph poles' and Ford recalls a lot of dialogue. Producer Ed Stradling provides some background into Donald Wilson's decision to cut the serial down from four to three episodes ('he actually lost 'The Urge to Live' while watching it' is a very amusing way of putting it) and he and Toby Hadoke discuss how they decided to reconstruct the missing material from the edit of episodes three and four using Ford, Russell and a troupe of impersonators, footage, photographs and animation.

Suddenly Susan (15:19)

Carole Ann Ford regrets how the original intentions for the character of Susan - 'tremendously athletic a la The Avengers', 'very stylistic with an amazing wardrobe' and 'extraordinarily intelligent' - were never fully realised. However, she's pleased she got a Vidal Sassoon haircut and managed to smuggle in a bit of Mary Quant. She chats about her relationship with Hartnell, his paternalism and the edge to his performance, described 'like an unexploded bomb'. She describes how the series was made and produced (and Verity's unique position as producer at the time), the script changes and recording, Marco Polo and The Keys of Marinus (practical jokes ahoy!) and the physical endurance required working on Planet of Giants. Originally recorded for 2003’s The Story of Doctor Who.

The Lambert Tapes (14:01)

Doctor Who’s original producer Verity Lambert discusses casting the Doctor as 'a grown up child' and being inspired by Hartnell in This Sporting Life and The Army Game; Susan becoming the Doctor's granddaughter and the difficulty of replacing her; the tiny budget of £2,000 per half hour and how her ingenious art department created weekly miracles, the limitations of working at Lime Grove and the development of those iconic titles and music. Wonderful recollections from a television legend recorded for 2003's The Story of Doctor Who.

Prop Design Plans (DVD-ROM)

Cusick's drawings for the 'top edge of sink', 'corner of briefcase' and 'telephone top'.

Radio Times Listings (DVD-ROM)

Doctor Who: Planet of Giants

BBC Worldwide / Released 20 August 2012 / BBCDVD 3479 / Cert:U

BBC 1964

3 episodes / Broadcast: 31 October – 14 November 1964 / Black & white / Running time: 73:42

Whitaker commissioned Robert Gould to develop the scripts in September 1963 but by 4 February 1964, Gould's work on the now titled The Minuscules was proving problematic and Whitaker requested that he abandon the scripts. On 23 March, Whitaker commissioned Louis Marks to provide a new 'minuscules' storyline and by May he had been formally contracted for the four scripts of Planet of Giants. Marks had found inspiration in the recent publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring. Her investigation into the effects, particularly on the food chain, of chemical pollution and the over-use of insecticides such as DDT had 'caused a considerable stir' and 'as miles of fields and farmlands disappeared beneath motorways, housing estates and tower blocks, people were beginning to question the post-war emphasis on economic growth and scientific progress'. (4)

a period when 'the grammar of television accelerated'Marks wove together the previous elements of the The Minuscules - the TARDIS crew lost in an over sized house and garden - with what Verity Lambert disparagingly called a 'Tales of Scotland Yard' sub-plot involving government scientist Farrow, his aide Smithers and cruel industrialist Forester. The plot details the lengths that Forester will go to in getting government approval for his insecticide DN6 and that includes murdering Farrow and colluding with Smithers to doctor Farrow's negative report on the DN6 trials. To emphasise the domestic milieu in which this story takes place he also introduces the local telephone exchange operator Hilda Rowse and policeman husband Bert as sympathetic foils for the audience and the efforts of the TARDIS occupants to thwart Forester.

Not only was Marks reflecting the concerns raised by Carson's book but he was also following in a tradition of 'resizing' in popular fiction and culture - everything from Carroll's Alice in Wonderland and Mary Norton's The Borrowers to the B movie machinations of Dr. Cyclops (1940) and Richard Matheson's sublime The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). The 'Tales of Scotland Yard' aspect of the story also resembles the 50 minute 'bobby on the beat' drama Dixon of Dock Green, one of the BBC's most successful long running dramas and, at the time, grabbing 13 million viewers on a Saturday night. Tat Wood and Lawrence Miles explain how this format was already looking anachronistic within a series such as Doctor Who and during a period when 'the grammar of television accelerated' and a production such as Z Cars was already ringing the changes where it had 'been estimated that the average length of a shot in an episode... was twelve seconds.' As they suggest, 'That's almost subliminal by 1962 standards'. (5)

It is therefore not surprising that the man handling the complexities on this serial was Associate Producer Mervyn Pinfield, a former member of the Langham Group, a short lived 'experimental television group' led by Anthony Pelissier which attempted to develop the aesthetics of television and move it away from its theatrical origins. It was an R&D opportunity for Pinfield to work on inlay, overlay and split-screen techniques and several groundbreaking dramas, including Torrents of Spring (tx 21/05/1959), had been made by the group. Many of these techniques filtered into the likes of Z Cars and Doctor Who. At the suggestion of Pinfield, Verity Lambert and Bernard Lodge had watched the 'howl-around' footage that a technician called Ben Palmer created for Amahl and the Night Visitors, a drama broadcast in 1951, when they were experimenting with similar effects for the opening titles of the series.

Pinfield was training other directors in such techniques and was the go-to-guy if a Doctor Who serial held a particular technical challenge. He directed all but one of the episodes of Planet of Giants with the fourth, 'The Urge to Live' handed over to Douglas Camfield. Camfield had been working on Doctor Who as film editor and production assistant, previously shooting and editing a number of sequences for An Unearthly Child and Marco Polo, and he would become one of the series' most prolific directors. In terms of television pacing, Camfield's work on the fourth episode of the serial, then called 'The Urge to Live', and his requirement to edit together this and the third episode 'Crisis' is also an indication of how much faster television would become as directors became confident with new production techniques.

'... we could not do everything we wanted to do to make it wholly satisfactory'Planet of Giants was then made as part of the first series' production block and initially was held over as the second story to be transmitted in the proposed second season. The score was recorded between 14 and 25 August and heralds the arrival of composer Dudley Simpson to the fold. Simpson, had, before leaving Australia, composed for the Borovansky Ballet Company, forerunner to the Australian Ballet and his association with Doctor Who would eventually open up an entirely new career in composing title themes and incidental music not only for the series but for many other television programmes.

Whitaker and producer Verity Lambert had also managed to get the production moved to Television Centre and on 21 August recording took place for the first episode in TC4 after visual effects inserts had been filmed at Ealing between 23 and 30 July. The following three episodes were recorded on each Friday between 28 August and 11 September. Sound mixer Alan Fogg 'pre-recorded several segments of specially speeded up or slowed down soundtrack to show how, comparatively, a tiny voice sounds to a giant, and vice versa'. (6)

The move to TC4 enabled designer Ray Cusick to manage the technical challenges of creating giant sized props such as matchboxes, earthworms and ants in Farrow's garden and, later, his standout work recreating a briefcase, the sink and its plughole. The serial also had to deal with 'precisely lined-up inlay shots, half-silvered mirror shots, glass shots and back-projections to overcome the great hurdle of having the travellers and the 'giants' in the same shot'. (7)

Cusick created the first ever glass shot for the series to extend the ground floor of the house and the production used front projection techniques to show the TARDIS crew interacting with Farrow's body, a rack of test tubes and a telephone. He allegedly also came up with the idea of using the gas-jet to attack Forester. It's worth noting that these over sized props, sets and effects were achieved on a shoestring budget well before Irwin Allen threw a ton of cash (a reported $250,000 per episode) at his Land of the Giants television series when it started shooting in Autumn of 1967.

Donald Wilson would have preferred leading off the second season of Doctor Who with The Dalek Invasion of Earth but the departure of Carole Ann Ford at the end of that story made it impossible to swap the two serials around. He was also of the opinion that Planet of Giants would benefit from editing. In a memo to Sydney Newman on 19 October, he noted: 'I am arranging to reduce the four-part serial entitled Planet of Giants to three parts. This is the'minuscule' story with which we must begin our new season and I am not satisfied that it will get us off to the great start that we must have if it runs to its full length. Much of it is fascinating and exciting but by its nature and the resources needed we could not do everything we wanted to do to make it wholly satisfactory'. (8) The last two episodes were transferred to 35mm film and Camfield edited them into one episode 'Crisis'.

The story is atypical for an Earth based adventure of the period in that its setting is contemporary and the threat is contained within the domestic environs of a house and garden. It's also commendable that it taps into environmental concerns, perhaps more relevant now than then, and Rachel Carson's widely credited influence on the environmental movement and widespread public concerns about pesticides in the face of industry disinformation and government's own failure in uncritically accepting industry claims.

Representing the disinformation and industry bluff are the 'villains' Farrow, Forester, Smithers and for DDT we have DN6. However, the dubious business practises of industry are only marginally explored and the editing of the third episode, while adding pace after two rather slow episodes, doesn't add any clarity to an already under-developed sub-plot. Farrow is played unremarkably and briefly by Frank Crawshaw but Alan Tilvern as Forester, is rather sinister and oily. There is some confusion over his motivation - he apparently developed DN6 but doesn't seem to have a clue who will manufacture and distribute it despite having killed Farrow and eventually gunning for Smithers too. The missing material from the original edits of 'Crisis' and 'The Urge to Live' briefly touches on this.

These conventions also include Bert and Hilda Rowse - the couple at the telephone exchange - who would have had the familiarity of characters from the likes of Dixon Of Dock Green and, indeed, the way the story turns from industrial espionage to village scandal does echo the weekly homilies dished out by George Dixon and company. Both characters feel like they've strayed out of an Ealing comedy and it is rather convenient for the story that Hilda, the exchange operator, is married to the local bobby. Even though the missing material does feature them it is understandable why Donald Wilson had it excised as it mainly revolves around Hilda's concerns about Farrow's phone being off the hook.

With three sets of characters - Forester and Smithers, Hilda and Bert, and the TARDIS crew - that rarely interact, Planet of the Giants does have its fair share of dull patches. The real joy of the story lies in the regular characters exploring their over-sized environment, beautifully realised despite the infancy of modern television production and technology, and how the characters, despite their size, go beyond simple exploration and seek to call attention to the harmful effects of the insecticide. Pinfield's direction offers up some little treats too. The slow pull back from the TARDIS, tucked away in the crazy paving of the garden, to a master shot of the garden and the house is a technically ambitious shot and his ability to match over sized props and actual props through zooming and editing works very well.

If there is a central figure worth watching this serial for then it has to be Jacqueline Hill as Barbara. Yes, you may end up berating Barbara for her singular failure to let her friends know that she has been infected by DN6 but Hill is rather brilliant at equally conveying the character's failure to do so. Her silent terror as she is frozen to the spot by the appearance of the giant fly is a stand out moment. The puppet effects for the fly are also, for their time, exceptional even if the prop was one borrowed from the Visual Effects Department and not created specifically for the production. Barbara does get turned into something of a shrinking violet (pun intended) on the one hand and someone who over-reacts on the other but Hill does manage to keep her fate compelling throughout.

She works well with Hartnell, whose performance has transformed the Doctor from the aggressive misanthrope of An Unearthly Child, and their domination tends to put Carole Ann Ford and William Russell into the shade. Ford rightly argues that her character wasn't written well and she's not wrong here. Russell is also written more or less as the brawny but resourceful school teacher hero figure and lacks development as a character.

After a season of stories where the Doctor has attempted to get Ian and Barbara back to Earth in 1963, he finally achieves it here and the pair of them, and the story, barely acknowledge this fact. Contemporary Earth settings will, of course, become a vital component of the series as it progresses into the later 1960s and into the 1970s and it is interesting to see how this is treated as almost a separate element in theDoctor Who format at this point.

What impresses most is, for the time, the stunning production design and visual effects from Ray Cusick. It really is a triumph of design that turns this exploration of a threatening domestic space into a realm of the uncanny. Here, the ordinary is made extraordinary - it's a World's Fair (as Ian at first rationalises it) of giant earthworms, ants and bees where evil and the unknown are embodied by drainpipes, sinks, plugholes, telephones, cats, matchboxes, seed packets and briefcases. Where else would the image of a man washing his hands in a sink create a terrifying cliffhanger to a drama?

(1) BBC Archive - The Genesis of Doctor Who

(2) Laurence Marcus, Television Heaven: The Origin of Doctor Who

(3) Howe, Stammers and Walker: The Doctor Who Handbook - The First Doctor

(4) Dominic Sandbrook: White Heat

(5) Tat Wood & Lawrence Miles, About Time 1963-1966

(6) Jeremy Bentham: Doctor Who - The Early Years

(7) Ibid

(8) Howe, Stammers and Walker: The Doctor Who Handbook - The First Doctor

Special features

Commentary

Moderated by Mark Ayres with vision mixer Clive Doig, special sounds creator Brian Hodgson, make-up supervisor Sonia Markham and floor assistant David Tilley.

Episode 3 and 4 Reconstruction (52:38)

Using the original scripts, newly recorded dialogue and animation, this feature gives viewers an idea of how the original four-part version might have appeared. On the positive side, the efforts of all involved must be applauded. The newly recorded audio matches are often incredibly good and combining these with existing footage and some modest pieces of animation produces a refined, more professional version of the kind of re-cons that fans have been making and watching for years. However, you can't create a silk purse out of a sow's ear in this instance and there's a very good reason why Donald Wilson decided to edit the two episodes into one.

The missing twenty five minutes are not the finest example of early Doctor Who and are perhaps rather atypical of even this period of the programme's output. There are many longueurs, particularly the exchanges between Forester and Smithers about disposing of Farrow and tampering with his report and the comedy Dock Green exploits of Hilda and Bert. As Carole Ann Ford correctly recalls, this is very dialogue heavy and that is emphasised by this reconstruction. The extension to the scene of the TARDIS crew mapping Farrow's notebook is a case in point. It just holds up the narrative for nearly a minute and a half. Many of the scenes involving Forester, Smithers, Hilda and Bert are simply repetitive. However, the poisoning of the cat, the Doctor's resolve to save the Earth and Barbara's emotional melt-down are good scenes and it's a pity they were consigned to the cutting room floor or were truncated. Some of the missing material does create some logistical problems in the existing edit of 'Crisis' but Wilson's decision seems, in retrospect, a wise one.

It's a laudable experiment, done for the right reasons and, while the material isn't the most engaging and we can understand why it never made it to the screen, this does perhaps create a viable template for potential re-cons on future DVD releases.

Rediscovering The Urge to Live (8:30)

Ian Levine explains the origins of Planet of Giants and how the concept was developed and finally realised. Also on hand are Carole Ann Ford and William Russell. Bill's entire memory of the show is 'a box of matches' and 'matches like telegraph poles' and Ford recalls a lot of dialogue. Producer Ed Stradling provides some background into Donald Wilson's decision to cut the serial down from four to three episodes ('he actually lost 'The Urge to Live' while watching it' is a very amusing way of putting it) and he and Toby Hadoke discuss how they decided to reconstruct the missing material from the edit of episodes three and four using Ford, Russell and a troupe of impersonators, footage, photographs and animation.

Suddenly Susan (15:19)

Carole Ann Ford regrets how the original intentions for the character of Susan - 'tremendously athletic a la The Avengers', 'very stylistic with an amazing wardrobe' and 'extraordinarily intelligent' - were never fully realised. However, she's pleased she got a Vidal Sassoon haircut and managed to smuggle in a bit of Mary Quant. She chats about her relationship with Hartnell, his paternalism and the edge to his performance, described 'like an unexploded bomb'. She describes how the series was made and produced (and Verity's unique position as producer at the time), the script changes and recording, Marco Polo and The Keys of Marinus (practical jokes ahoy!) and the physical endurance required working on Planet of Giants. Originally recorded for 2003’s The Story of Doctor Who.

The Lambert Tapes (14:01)

Doctor Who’s original producer Verity Lambert discusses casting the Doctor as 'a grown up child' and being inspired by Hartnell in This Sporting Life and The Army Game; Susan becoming the Doctor's granddaughter and the difficulty of replacing her; the tiny budget of £2,000 per half hour and how her ingenious art department created weekly miracles, the limitations of working at Lime Grove and the development of those iconic titles and music. Wonderful recollections from a television legend recorded for 2003's The Story of Doctor Who.

Prop Design Plans (DVD-ROM)

Cusick's drawings for the 'top edge of sink', 'corner of briefcase' and 'telephone top'.

Radio Times Listings (DVD-ROM)

Production Information Subtitles

Grand collection of production trivia that explores the development of the script and production of the serial all expertly compiled and written by Matthew Kilburn. Photo Gallery

Good collection of black and white stills, some great images of the sets, props and effects. Coming Soon Trailer

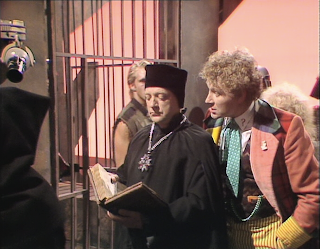

A trailer for the Vengeance on Varos Special Edition... Digitally remastered picture and sound quality

There's even an Arabic version of the soundtrack available Doctor Who: Planet of Giants

BBC Worldwide / Released 20 August 2012 / BBCDVD 3479 / Cert:U

BBC 1964

3 episodes / Broadcast: 31 October – 14 November 1964 / Black & white / Running time: 73:42