'I'd like you to know how moved and impressed I was by your play, A Night Out, this past Sunday. It has an intensity and inner truth both horrifying and purgative. There are few things, if any, I have seen on British TV that can compare with it. Congratulations.' (1) An extraordinary collaboration between writer Harold Pinter and film director Joseph Losey, one which would eventually stretch across three film projects, was initiated with the above letter sent by Losey to Pinter.

It was despatched after the transmission of the play in ABC's groundbreaking Armchair Theatre series on 24 April 1960, three days before the opening at the Arts Theatre of what was considered Pinter's breakthrough success in the theatre, The Caretaker. Up until that opening, Pinter's reputation for crafting his signature 'comedy of menace' had been formed in a handful of plays including The Room, The Birthday Party and The Dumb Waiter.

It would be two and half years later before Pinter and Losey worked together on The Servant, an adaptation of Robin Maugham's sixty-two page novella published in 1948. The rights to the book had been purchased by director Michael Anderson who then commissioned Pinter to write a screenplay in 1961. Losey had also expressed an interest to Maugham about a stage adaptation as early as 1955. Anderson failed to raise the necessary finance and, in the meantime, Dirk Bogarde had received and read the first Pinter screenplay. Writing in his biography Snakes and Ladders, Bogarde recalls his excitement about Pinter's script, declaring it had 'the precision of a master jeweller... his pauses are merely the time-phases which he gives you so that you may develop the thought behind the line he has written, and to alert your mind itself to the dangerous simplicities of the lines to come'. (2)

Even in England, he still felt the after effects of his accusers. He worked under the name of Victor Hanbury on The Sleeping Tiger because stars Alexander Knox and Alexis Smith felt they would be tarred with the same pro-Communist brush if they worked with him. He also had to back out of directing X The Unknown (1956) for Hammer because star Dean Jagger refused to work with a Communist sympathiser.

Bogarde's orbit aligned with Losey's when he was casting The Sleeping Tiger. He saw Bogarde in Hunted (1952) and claimed 'I'm going to do this picture with Dirk Bogarde and nobody else'. Initially Bogarde was unsure of Losey and got a sense of the director's problems when he had to bundle him out of a Shepperton hotel after an alleged, and potentially disastrous, encounter with the reactionary anti-Communist mother of Ginger Rogers. Bogarde found it an uneasy relationship but saw in Losey something of a kindred spirit. After Losey had brought Bogarde's attention to Maugham's novella in the mid-1950s, it was Bogarde who alerted Losey to the Pinter script while the director was on location in Rome filming Eve (1962). (3)

However, like Michael Anderson, Losey found it near impossible to raise finance for the script of The Servant. It was eventually Leslie Grade, a talent agent with The Grade Organisation, who backed the film having made a tidy sum from two Cliff Richard films, and co-financed it with ABPC and the National Film Finance Corporation. Anderson was paid £12,000 for the rights but then other hurdles presented themselves.

Bogarde's partner and manager Tony Forward worried that the role of Hugo Barrett, the manservant to upper class Tony, would harm Bogarde's career as The Servant seemed to be just another 'completely homosexual picture' so soon after his breakthrough role as the closeted bi-sexual barrister Melville Farr in Basil Dearden's Victim (1961). (4) Bogarde, uneasy about the role, even suggested Ralph Richardson for Hugo Barrett but Losey informed him Richardson was too expensive and 'you'll have to do.' (5)

Pinter's script removed the single narrator of Maugham's melodramatic novella and 'its yellow book snobbery and the arguably anti-Semitic characterisation of Barrett - oiliness, heavy lids - replacing them with an economical language that implied rather than stated the slippage of power relations away from Tony towards Barrett'. (6) Both Losey and Bogarde later refuted the homosexual reading placed onto the film, one perhaps traced back to the strange incident between Maugham and his own servant that inspired the original novella, and preferred to see the relationship between Tony and Barrett as one defined by sadism and domination.

In terms of power relations, Pinter and Losey didn't exactly hit it off in an initial meeting when Losey presented the writer with notes to rewrite the script. After suggesting Losey should go and make another film, the director tore up the notes and they agreed to start again, from then on developing an intense collaborative working partnership where 'material from the script was rarely simply excised wholesale. Instead it was transposed, concentrated or dispersed'. (7) The original 1961 script was revised and the final version prepared by January 1963.

Ealing alumnus Norman Priggen, an assistant director on Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) and The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) among others, was hired as co-producer and his relationship with Losey matured into a production partnership lasting over seven films. Designer Richard Macdonald, who had worked with Losey on The Sleeping Tiger and Eve, created the meticulous interiors of Tony's Chelsea house at Shepperton.

While the studio housed the claustrophobic amalgam of rooms built around a central staircase, exteriors were shot in Royal Avenue, with Tony's house opposite Somerset Maugham's former home, King's Road for the opening titles and our first view of Barrett outside Thomas Crapper's premises, and Chiswick House to stage Tony and his girlfriend Susan's weekend at the Mountsets' home.

Bogarde recommended the twenty-three-year-old James Fox to Losey for the role of Tony after seeing him in an ITV Play of the Week, 'The Door' (transmitted 20 May 1962), acting under the name of Oliver Fox. He phoned Losey to try and catch the rest of the play after Bogarde, later recalled, saw something in Fox: 'Under the grace and breeding, the golden-boy innocence, I sensed, and I don't for the life of me know why, a muted quality of corruptibility. This young man could spoil like peaches; he could be led to the abyss.' (8)

As Fox recalls in the DVD interview in this edition, it was a serendipitous route to casting the film. He was going out with Sarah Miles, whom Bogarde had already approached to play Barrett's 'sister' Vera in the film, and their agent was his father Robin Fox, who also happened to be Losey's agent. Miles and Fox met Bogarde at the premier of The L Shaped Room and she also suggested Fox for the part.

It was mutually agreed both Miles and Fox would be excellent casting but their relationship, already deteriorating, eventually caused Losey some problems on set. During the infamous scene of Vera's seduction of Tony on a leather chair, she branded Fox a 'great stinking queer' for wearing a combination of karate dressing-gown and fur boots for the scene. Her agent Robin Fox had words with her, Losey gave her an ultimatum and Fox completed the scene sans fur boots. (9)

Fox recalls a crude, silent screen test with Losey, paid for by the director, shot in a flat in Queen's Gate and writer Paul Mayersberg claimed Fox's inexperience generated many retakes until Losey found what he wanted and he and editor Reginald Mills then shaped the performance in the cutting room. Wendy Craig's casting as Susan, Tony's girlfriend, was again via Dirk Bogarde's suggestion after working with her on Basil Dearden's The Mind Benders (1963) but she was often regarded by Losey as the weakest link in the ensemble.

Shooting began on 28 January 1963 with celebrated British cinematographer Douglas Slocombe as a replacement for Losey's original preference of Christopher Challis. Slocombe, an Ealing veteran of, among others, It Always Rains on Sunday (1948), Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), The Man in the White Suit (1951), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), Mandy (1952)and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953) devised a four phase lighting scheme for the film to highlight the deterioration within the house.

The shoot was interrupted a fortnight later when Losey was incapacitated by pneumonia and, in his ten-day absence, he asked Bogarde and Richard Macdonald to continue shooting to his script specifications. On his return, wrapped in blankets and hot-water bottles, he directed from a bed and, apart from three scenes, reshot everything that Bogarde and Macdonald had filmed.

Mills efficiently produced a rough cut immediately after the end of filming on 19 March 1963, editing the film as it was being shot. Pinter was affronted by Mills's trimming back of his repetitive dialogue and he also sent a very angry letter to Mills after some rather condescending and disingenuous comments the editor made about him in an interview and told him succinctly 'to go and fuck yourself'. With post-production complete and a clean bill of health from the British Board of Film Censors (despite some minor concerns over Tony's seduction of Vera in the leather chair after a screening with John Trevelyan), Losey then struggled to get distributors interested in The Servant, which he proudly claimed was 'a remarkable film'. (10)

Even though it was one of three British films represented at the Venice Film Festival, it was considered unreleasable until Warner Brothers' European booker Arthur Abeles, left with a gap in his release schedules, found a home for it in the Warner Leicester Square where it aptly received its British premier on 14 November 1963 some five months after the climax of the Profumo scandal.

Barrett has an agenda, subtly revealed to begin with as he begins to tastefully decorate the house and minister to his master's needs. However, Tony's fiancée, Susan, detects an undercurrent in Barrett's relationship with Tony and a battle of wills ensues over who will have sovereign power - of Tony and of the house. Class and power are transmogrified, as Barrett's 'sister' Vera arrives to seduce Tony and allow Barrett's agenda to move into full gear.

A working class revolution takes place, the servant and the master swap places as power fragments and reforms and the bright white Chelsea house is filled with shadows, becomes a prison cell possessed by a demonic, corrupting force which prompts Tony's slide into a hell of Barrett's construction.

This devious plan is played out in the film as a series of distinct acts and where set decoration, lighting, the placing and use of objects, costume and music essentialise the transformation of a servant's deference into a domination over his master. Performance and dialogue also trace this release of, what Colin Gardner refers to as, Barrett's primal force that grows in power and influence during the film.

The film describes a web in which various couplings are caught, presenting an interchange of power and domination between Tony, Barrett, Susan and Vera. The house becomes a series of doorways into a labyrinth, one gradually diminishing and pushing the exterior world away. Losey continually places characters in doorways, emerging into or out of rooms to denote the shifting of power, providing a visual analog to the interior of the psyche, where all the characters peer into or out of rooms or are caught in reductive, distorting mirrors.

The film opens with the black figure of Barrett walking towards Royal Avenue, passing by the showroom of Thomas Crapper where Losey's camera lingers on the 'by appointment' coat of arms on the shop front before pulling back to reveal the name of said sanitary engineers and Barrett crossing the road outside. The sign of royal approval, of status, is contrasted with the figure of Barrett, who 'emerges from the primordial depths of the toilet, like some backed up excremental waste.' (12)

In a simple but witty sequence, he is already a representation of the filthy tide now about to wash up on the shores of Tony's indulgent respectability. Tony as an 'imperialist project' is also symbolised in the pipe dream of clearing the jungles of Brazil to build three cities where he'll be able to grant the peasants a new life. He refers to Barrett as a peasant towards the end of the film, long after his dream has failed and said peasant has revolted.

Barrett's first encounter with Tony, at the empty house, is equally a signifier of things to come. Losey holds on a shot of Barrett gazing up the central staircase. The staircase is a pivotal emblem of the battleground in the house, the shifting escalation of dominance and power and the rooms off it giving characters the power to reconfigure vertical and horizontal space. Barrett finds Tony asleep, a supine physical condition which Losey repeats throughout the film. Tony is rarely upright. He's either lying down or slouched in a chair. In the climax, he's crawling on his knees or slumped in a corner.

The three o'clock interview which assesses Barrett's suitability to be a manservant ('Well, my… my soufflés have always received a great deal of praise in the past, sir') also reveals Barrett to be not quite what he seems when he slips up in his distinction, pointed out by Tony of course, between Viscount or Lord Barr.

As Bogarde noted of the character's deception: 'Barrett's a liar... if you know what a gentleman's gentleman is like, you'll know Barrett could never have been one. I don't think he'd ever made a soufflé in his life.' (13) Even the workmen decorating the house can detect the mutton dressed as lamb as Barrett attempts to better himself to the detriment of these other working class figures.

Decor and taste are also markers in the field of battle. As designer Richard Macdonald recalled of the transformation of the house: 'at the beginning it is an empty shell, it's cold and has no personality; then it's suddenly painted and beautified; then it gradually rots; and then at the end it takes on a completely new personality, it's partially repainted, it has black ceilings and a gaudy, meretricious look in everything.' (14)

Barrett initially oversees a white and blue scheme for the house, filled with tasteful neo-classical objects and paintings. There is a tug of war between Susan and Barrett over who is the arbiter of taste and style in the house, over the installation of a 'proper spice shelf for the kitchen', the placing of flowers, objects and the removal of 'chintz frills'. Objects move around the house: the contents of Barrett's room upstairs creep into the drawing room downstairs as the decor becomes darker, satanic. Neoclassical vases and figures briefly materialise into alcoves, a reminder of the frozen in aspic poses of Lord and Lady Mountset we see during Tony and Susan's weekends away where class is determined not by the possession of a spice rack but by defining what a poncho is.

A muscled male bronze seems to signify a homoerotic, passive aggressive tension exuded by the two men and its position alters in the film from the top of a display cabinet to a sideboard. When Tony receives the gift of a karate style dressing-gown, Barrett glances back to look at it but might as well be gazing at the bronze positioned in between them judging by his adulation of 'it's very handsome, sir.'

A parallel to the bronze can also be seen in the muscle magazine pictures pinned to the wall of Vera's room and what look like sketches of male nudes in Tony's study. An early and witty indication of the manipulation of masculinity in the film can also be seen in Barrett's preparation of a bowl of hot water for Tony's feet. Not only does he infuse the water with the appropriately named 'Stag' salt but he also bows and scrapes, pulling off Tony's socks, as his master hurls a veiled insult at him, 'You're too skinny to be a nanny, Barrett.'

Underlining the various items of military paraphernalia - portraits, statues and cannons - which form the decor, there's also the double entendre in a later scene when Barrett, serving Tony some mulled claret, notes he was known in the army as 'Basher Barrett' because 'I was a very good driller.'

When Barrett has finally claimed Tony's soul at the end of the film, Tony fawns to him, 'I have a feeling we’ve always been buddies.Like the Army.' The ball games they play on the stairs, when deference has gone out of the window, also carry a sublimated homosexual charge, especially when Barrett complains of an injury received from the ball: 'I'm not staying here in a place where they just chuck balls in your face.'

Slowly, inexorably Barrett dominates, passing through the veneer of class and deference as easily as he slips through the doorway disguised as a bookcase that separates the drawing room, the space of privilege, from the kitchen, the engine of domesticity. His character continually shifts between these spaces.

Note his obsequious demeanour when Susan first comes to visit and mocks his pretensions as he serves wine while wearing white gloves ('Italian, miss. They're used in Italy' to which she replies, 'Who by?') and then, in direct contrast, observe his post-supper slump among the dirty dishes, picking his teeth, downing Guinness, blowing cigarette smoke and idly throwing the white gloves to one side as his gimlet eyes suggest a dark plan already being formulated.

The signature convex mirror, a reflection of the claustrophobia in the house, also first appears before the supper scene and is a symbol of Barrett's trap, where all the figures who enter the room are eventually crushed within its warped reflection. Other distortions and reflections occur: Barrett calling for Vera to be introduced to her master is shot through a huge brandy glass, military photographs surround Tony adjusting his tie in a mirror and Vera's seduction of Tony is caught in the shiny surfaces of kitchen appliances.

Cigarette smoke is another visual code in the film. Characters exhale great clouds of it as they contemplate their powerful deeds, many of them sexual, or their machinations in gaining superiority over one another. Vera seductively allows a glob of smoke to escape from her lips when Barrett gets familiar with her on the kitchen table, the first suggestion of the incest which will shock Tony and Susan later but which turns out to be another of Barrett's deceptions in the film.

It marks intimacy between Susan and Tony when we see them lying side by side in the drawing room, listening to the Cleo Laine title song. Their coupling is all too brief when Barrett oversteps the mark by disturbing them, confirming Susan's view of Barrett as a demonic entity, who appears at will like 'a Peeping Tom' or as Tony mocks, 'a vampire too on his Sundays off'. She resents his dominance and the rest of the film is a tug of war between them for the possession of Tony's soul. In the film's bleak conclusion, Barrett blows a huge cloud of cigarette smoke into Susan's face, to mark her defeat and humiliation in the scheme of things.

The central staircase records the progress of the war. Losey frames a shot of Barrett dusting the bookcase in the foreground and Susan peering down at him from the first floor as a prelude to the scene where she brings flowers into Tony's bedroom during a spell of illness. When Barrett tries to remove the flowers, and we see him in the mirror first as he enters the room, she simply barks 'put that down', reaffirming her exercise of power. However, in one of the film's great exchanges of dialogue, Barrett undercuts her as she leaves the house. 'I'm afraid it's not very encouraging, miss...' he pauses, '...the weather forecast'.

That very British sensibility of talking about the weather is married to a veiled insinuation about their ongoing stormy relationship it seems. As he closes the door, watch his self-satisfied smirk. It's Bogarde briefly and brilliantly revealing the man's satanic depths. She holds on to a lamppost outside, clearly troubled by the skirmish. Losey doubles this shot later, at the film's end, when in the final humiliation dealt by Barrett, she runs from the house and clings to a tree, sobbing.

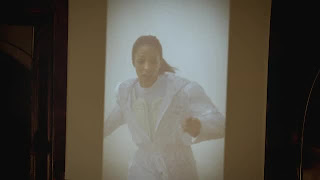

Vera's manipulation by Barrett, after he invites her to London, is reflected in Barrett's treatment of women in general. As he phones Vera, his forward planning underlined by a terse, 'Vera, are you ready?', he's assailed by an impatient woman outside the phone box. He first observes her legs but after she taps on the window with a coin, his hand slaps onto the glass and covers up her face. 'Are you being a good girl?' he asks Vera, clearly regarding the woman outside the phone box as the opposite, cancelling her assertiveness as a consequence of her being a 'bitch.'

Later, Vera herself is introduced with a close up of her legs as she and Barrett totter down the steps of St. Pancras. Losey brilliantly intercuts her arrival in London with a sequence between Susan and Tony set in a restaurant. Vera, wide-eyed at the sights of the big city and yet overly intimate in the way she holds onto Barrett's thighs in the taxi from the station, further suggesting an incestuousness to the 'brother-sister' relationship proposed at this stage, is given a blousy, seductive jazz theme by composer Johnny Dankworth.

As the instrument of Tony's destruction arrives, the restaurant hosts a series of intriguing variants on dominance and submission: bickering lesbians, a domineering bishop advising a younger cleric, a metropolitan couple. The down to earth Susan, trapped beneath the icy formality of the Mountsets and reluctant to sink into the hell occupied by Barrett and Vera, is reprimanded for judging Tony's choice to hire Barrett. Their relationship seems wounded at this point and, later, Vera's seduction of her man severely undermines it too.

Half way into the film, Barrett deploys his secret weapon to devastating effect, using Vera to reconfigure space wherein 'rooms that were once clearly demarcated as a haven or sanctuary are now the site of desecration and open trangression.' (15) The kitchen first presents working class sexual excess in an expression of short skirts, clouds of cigarette smoke and Barrett's sultry looks at Vera over a cup of tea. Vera then turns up in Tony's bathroom, undermining his casual misogyny of 'she is having a bath in my bathroom', and there follows a delicious scene where Barrett and Vera ape Tony's pretentiousness. 'I'm going to have a bath in his bathroom,' drawls Barrett as he briefly seizes control of Tony's inner sanctum, sits under a sun lamp and demands to be slathered in cologne.

Losey's control is at its finest in the moment when Vera finally gets her man Tony in the kitchen, under orders from an absent Barrett. They are accompanied to the pulse of a dripping tap and a ticking clock to signify Tony's dammed up, repressed sexual energy. 'In't it hot in here?' purrs Vera as she curls her legs up and sits on the kitchen table. The ticking clock is like a bomb about to go off and the spectre of Susan, a slowly receding representative of his pre-Barrett existence, is surely there in the unanswered telephone call as Tony advises Vera that her skirt is too short. Their lovemaking is reflected in the kitchen surfaces and the transgression is reinforced by Dankworth's sultry score.

'Did she manage to do anything for you, sir?' asks Barrett knowingly on his return and of the guilty looking Tony. Barrett reinforces guilt when Tony claims Vera was too under the weather to do the washing up and deliberately feigns mishearing, asking him 'Under the what, sir?' It's at this stage that Tony joins in the subterfuge, sending Barrett on a false errand for brown ale to not only give him time to get Vera out his room but to indulge in further sexual play. However, this time Losey specifically emphasises the trap and frames their embrace in the vortex-like convex mirror.

Following this is the seduction in the leather chair, a dominant and very masculine item of furniture which has already appeared several times in the film, and here bobs up and down to a ticking, chiming clock before Vera is enticed from her room by Tony to the strains of Laine's woozy, self-destructive and corrupting jazz number. At the same time, in a stunning reveal we see Barrett in her bed through the bars of the bannister as she descends the stairs.

Losey's shot of the stretched out, semi-naked couple in the chair is, of course, an analog to the iconic Christine Keeler photograph by Lewis Morley. The establishment-baiting image of her sitting naked with her legs enticingly spread around the back of the Arne Jacobsen chair to preserve her decency was taken at the height of the Profumo scandal, which had broken just as the film completed shooting.

Susan attempts once more to assert her status in the house, bossing Barrett around, rearranging furniture and flowers. It's like a tussle between a guardian angel and an impudent demon and one shot of Susan arranging the flowers, as Barrett reels from her insults, makes her look quite demonic as she demands, 'What do you want from this house?' He smirks at her and simply replies, 'I'm the servant, miss.' We know full well he's not just a servant, he's a revolutionary gradually knocking the foundations from under Tony's indolent sense of privilege.

Those foundations collapse completely when Tony and Susan find Barrett and Vera in their bed. Losey tangles together defiant shadows, the ever present staircase and the collapsing dimensions of the convex mirror wherein both couples are doubly reflected, doubly destroyed. The whiff of incest is dissipated, Tony's seduction by, and Barrett's relationship with, Vera is revealed. 'We shall have to tell our secret to Mr. Tony,' he concludes. This humiliation is compounded for Susan after Tony asks her to 'come to bed', to make love in the same bed still warm from Barrett and Vera's activities.

After dismissing the pair, Tony's world disintegrates and the house grows ever darker, unkempt and unloved. Tony sobs in Vera's bed beneath the wall plastered with muscle men pictures and we wonder just who it is he's missing - Vera or Barrett? Shortly after, a contrite Barrett spins his own sob story across the class divide in a pub, Losey's visuals demarcating Barrett's tale of mutual humiliation about Vera through partitions, bunches of flowers and beer pumps.

'She's living with a bookie in Wandsworth... Wandsworth!' he decries, the location clearly of more distress to him than her alleged infidelity. Losey is extremely clever here as the scene opens with the pub interior reflected in a mirror, is followed by a pan to Barrett in the foreground chatting to Tony and concludes with a reverse shot of the pub wherein the two men have swapped sides, a literal reversal of the relationship, a reversal of their status.

Barrett, with the upper hand, then employs his games to reduce Tony further. They bicker like a gay couple and Barrett reaffirms his dark origins in the criticism of all the 'muck and slime' surrounding him as he attempts to keep the now gloomy house in order and to make ends meet. Tony again lies supine on the couch, his dreams of creating cities in Brazil all but gone, as Barrett complains that 'butter's gone up tuppence a pound.' The decor changes (pointedly the spice rack is ripped off the wall), a more satanic atmosphere is generated, class warfare is in full flight ('I'm nobody's servant') and Barrett controls Tony through drink and drugs. Dankworth's music becomes more and more atonal and strained, echoing this nightmare.

The house is transformed into a baroque brothel, where orgies occur in an endless configuration of dark spaces reflected and refracted by mirrors, and Tony, when not deferring to Barrett or hiding from him in sheer terror, simply ends up crawling about his prison cell under the influence of 'something special from a little man in Jermyn Street' or viewing his world through a distorting crystal ball. The master-servant relationship is now based on a 'primordial, libidinally driven annihilation of sexual and class difference.' (16)

Vera returns, looking for money so she can go into hospital (suggesting a pregnancy perhaps), but this is yet another subterfuge. As Barrett seemingly kicks her out into the rain, Losey shows him smirking at Vera and shouting in mock indignation for Tony's benefit, 'get back to yer ponce'. He then shields her on the doorstep, hiding their conversation or furtively kissing her behind the front door. Vera reappears in the climax of the film, in the centre of the web, as Susan makes one final attempt to shock Tony back into reality, her trauma accompanied by the now nightmarish strings and discordant sax backing Cleo Laine's forlorn song.

Slocombe's lighting is high contrast, full of shadows and renders the end of the film intense, desolate and surreal and, while it may seem to be a triumph for Barrett as he climbs the stairs to the top of the house and runs his fingers along the bannister, you are left questioning what kind of revolution this is - if indeed it is about sweeping away the remains of privilege and class snobbery. The house becomes an hermetically sealed world where 'we are left with a sense of inertia rather than a promise of progress' and one symbolised by the stopped clock that Slocombe's camera closes in on just as the screen fades to black. (17)

(1) David Caute, Joseph Losey - A Revenge on Life

(2) John Coldstream, Dirk Bogarde - The Authorised Biography

(3) Ibid

(4) Ibid

(5) David Caute, Joseph Losey - A Revenge on Life

(6) Nick James, Joseph Losey & Harold Pinter: In search of poshlust times, Sight and Sound, June 2009

(7) Amy Sargeant, The Servant, BFI Film Classics

(8) John Coldstream, Dirk Bogarde - The Authorised Biography

(9) David Caute, Joseph Losey - A Revenge on Life

(10) Ibid

(11) Colin Gardner, British Film Directors - Joseph Losey

(12) Ibid

(13) Ibid

(14) Amy Sargeant, The Servant, BFI Film Classics

(15) Colin Gardner, British Film Directors - Joseph Losey

(16) Ibid

(17) Amy Sargeant, The Servant, BFI Film Classics

About the transfer

This is a very clean, sharp 1.66:1 restoration and is wonderfully detailed. Clothes, faces and objects look crisp and clear. Appropriate film grain is present and the contrast levels are layered in crisp whites, steel greys and deep black. The location sequences in the snow shine brilliantly in juxtaposition to the gradual darkening of the house interiors. Douglas Slocombe's exquisite, award-winning black and white photography is very well served by this truly handsome looking high definition picture. The mono soundtrack reproduces dialogue clearly and Johnny Dankworth's jazz score is well represented and there are no pops, crackles or warbles. This is altogether gorgeous.

Special features

James Fox interviewed by Richard Ayoade (45:26)

Director and actor Ayoade discusses the making of The Servant with actor James Fox, who played Tony. Various elements serendipitously came together as the film was cast. Bogarde apparently saw Fox on television and advised Joseph Losey of his potential for the role of Tony, and agent Robin Fox represented both Sarah Miles and James. Ayoade sometimes loses his thread in his questioning but he does pick up on some of the precision that Losey brought to shooting on the set and many of the themes about power and control in the film. Fox is a delight and his stories about his screen test are amusing and offer an insight into Losey's process and character.

Interview with Wendy Craig (5:26)

Craig chats about the British films of the 1960s and her reaction to the script. She believes the character of Susan is rather underestimated, contemplates the power struggle she has with Bogarde's character Barrett and her concerns about Fox's inexperience. Losey 'took his work very seriously' and she was apparently told off for handing out sweets to the cast and crew.

Interview with Sarah Miles (10:18)

She apparently demanded of her agent Robin Fox that she wouldn't play Vera without her then boyfriend (and Robin's son) James Fox in the cast. She was close to Losey and she explains that he allowed actors freedom because he wanted to concentrate on the atmosphere of the film and yet Miles and the rest of the team were very aware they were working on something quite special. She is particularly funny about inverted snobbery in the acting profession and her hotel calamity on the New York promotional tour for the film.

Interview with Stephen Wooley (10:34)

The director and producer recalls the BBC television showing of The Servant when he was a teenager and saw it as part of his introduction to world cinema. Believing it to be a 'truly odd film', he comments on the casting of Bogarde, his first encounter with Pinter, the black and white cinematography, the impact of the Vera and Tony seduction scene and the film's implications for class distinction. As an interview it's a tad dry.

Harry Burton on Harold Pinter (13:02)

Burton is the director of Channel 4's excellent documentary 'Working with Pinter' and here provides biographical detail about Pinter and his journey from actor to screenwriter, eventually dropping out of RADA to study the microcosm of people's lives in his writing. Burton explains that Pinter was very interested in the politics of class and privilege and had a political consciousness from his earliest days that fed into the highly charged The Servant and its challenge to the status quo. An absorbing if brief bit of context about the intense collaboration between Pinter and the leftist Losey that had its roots in the television screening of Pinter's 'A Night Out', about his screenplay and his appearance in the film.

Bogarde biographer John Coldstream on Dirk Bogarde(18:37)

'The most enigmatic and complicated person I've ever come across', offers Coldstream of Bogarde. He describes Bogarde as a difficult but charming man with whom he spent four years assembling a biography and book of letters. He was always a reliable friend if you were in trouble and was always on the look out for stimulating projects and he found a perfect collaborator in Losey who went on to change his career. Coldstream's analysis of Bogarde's key films is fascinating and he sees The Servant as the step into 'art cinema' that Bogarde wanted to achieve and Losey and Borgarde as 'European' rather than natives of their own countries. In a very rewarding interview, he also covers the origin of the Pinter script, its journey to Bogarde and Losey, the uneasy first meeting between all three and Bogarde's standing in for an ill Losey for the first week of shooting and, finally, Bogarde's account of 'creating' Barratt from his biography 'Snakes and Ladders'.

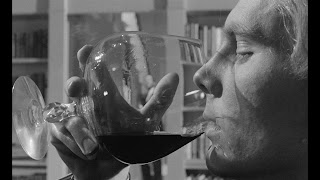

Audio Interview with Douglas Slocombe (19:18)

A splendid Matthew Sweet interview with legendary cinematographer Slocombe at home in October 2012. This discusses the 'chamber drama' of The Servant and Losey's fascination for the class system in Britain, Slocombe matching between the exterior shoot at a house in Chelsea and the interiors completed at Shepperton. The sets also allowed him some flexibility for manipulated light and shadow during the shoot, particularly for the now iconic scene of Tony and Susan watching Barratt's silhouette on the staircase and Sweet also picks out the distorting effect of the mirror as another visual key to the film. Slocombe discusses working with Bogarde, Fox, Miles and Craig and how the performances worked in tandem with Losey's intentions for the film's mise-en-scene with Slocombe lighting dripping taps and using surgical lamps. Sweet and Slocombe also chat about sexuality, class and power in The Servant and about how the film challenged the limits of permissiveness.

Joseph Losey and Adolfas Mekas at the New York Film Festival 1963 (27:58)

A very welcome piece of archive dredged up from a US television series called Camera Three featuring the festival organisers, Losey and fellow director Mekas, who had brought Hallelujah the Hills to the festival, in conversation. They begin with a discussion about the importance of film festivals and then after clips from The Servant, Losey is interviewed about the film. He's asked about the 'existence of evil' and the sado-masochistic and homosexual overtones in the film as well as its tragedy of class and privilege. The discussion switches to the visual power of the film and Pinter's minimalist script. A fascinating record of the film's initial reception and Losey's view of cinema.

Tempo (30:20)

An archive edition of the ABC arts show Tempo entitled 'Harold Pinter Playwright', transmitted on ITV 3 October 1965 and narrated by John Kershaw. Produced by director Mike Hodges, this examines the nature of Pinter's work as it focuses on sudden intrusions and threats to security, the foibles and faults of people and his ideas about which Pinter claims it's merely a 'job of work' to put the material together for plays that dictate their own destiny. It's an 'activity that he can't explain' and he 'just writes'. He's also obsessed by the order and rhythm of writing and how exciting and funny it is working with words. This interview is interspersed with clips, documentary footage and photographs and Kershaw delves into Pinter's background, education, encounters with anti-Semitism in Hackney, his status as a conscientious objector and his early acting career. A wonderful summation of his early work and there are great clips from the 1965 Peter Hall production of The Homecoming featuring Paul Rogers, Ian Holm, John Normington, Terence Rigby, Vivien Merchant and Michael Bryant.

Joseph Losey talks about The Servant (5:41)

Brief archive interview with Losey about the subject matter of The Servant, the casting and censorship of the film.

Stills gallery

Great set of behind the scene stills of Losey at work with the actors and a number of atmospheric portraits.

Trailer (2:38)

Stylish trailer from 1963 that uses Barrett's dialogue to Tony in the pub and Dankworth's theme song over a series of black and white stills and clips.

The Servant

Springbok Productions - Associated British Picture Corporation 1963

StudioCanal Blu Ray / Released 8 April 2013 / OPTBD0763 / Cert 15 / 115 minutes / Black and white

BD Specs: Region B / Feature Aspect Ratio: 1.66:1 / Feature Audio: DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 / Video Codec: MPEG-4 AVC / BD50 / 1080P / English Language / English, French and German subs

It was despatched after the transmission of the play in ABC's groundbreaking Armchair Theatre series on 24 April 1960, three days before the opening at the Arts Theatre of what was considered Pinter's breakthrough success in the theatre, The Caretaker. Up until that opening, Pinter's reputation for crafting his signature 'comedy of menace' had been formed in a handful of plays including The Room, The Birthday Party and The Dumb Waiter.

It would be two and half years later before Pinter and Losey worked together on The Servant, an adaptation of Robin Maugham's sixty-two page novella published in 1948. The rights to the book had been purchased by director Michael Anderson who then commissioned Pinter to write a screenplay in 1961. Losey had also expressed an interest to Maugham about a stage adaptation as early as 1955. Anderson failed to raise the necessary finance and, in the meantime, Dirk Bogarde had received and read the first Pinter screenplay. Writing in his biography Snakes and Ladders, Bogarde recalls his excitement about Pinter's script, declaring it had 'the precision of a master jeweller... his pauses are merely the time-phases which he gives you so that you may develop the thought behind the line he has written, and to alert your mind itself to the dangerous simplicities of the lines to come'. (2)

'This young man could spoil like peaches; he could be led to the abyss'Losey had worked with Bogarde on The Sleeping Tiger in 1954, Losey's first film made in England after he had left the US due to his blacklisting by McCarthy's instigation of the House Committee on Un-American Activities when his film The Boy with the Green Hair (1948) was brought to their attention for its pacifist tendencies.

Even in England, he still felt the after effects of his accusers. He worked under the name of Victor Hanbury on The Sleeping Tiger because stars Alexander Knox and Alexis Smith felt they would be tarred with the same pro-Communist brush if they worked with him. He also had to back out of directing X The Unknown (1956) for Hammer because star Dean Jagger refused to work with a Communist sympathiser.

Bogarde's orbit aligned with Losey's when he was casting The Sleeping Tiger. He saw Bogarde in Hunted (1952) and claimed 'I'm going to do this picture with Dirk Bogarde and nobody else'. Initially Bogarde was unsure of Losey and got a sense of the director's problems when he had to bundle him out of a Shepperton hotel after an alleged, and potentially disastrous, encounter with the reactionary anti-Communist mother of Ginger Rogers. Bogarde found it an uneasy relationship but saw in Losey something of a kindred spirit. After Losey had brought Bogarde's attention to Maugham's novella in the mid-1950s, it was Bogarde who alerted Losey to the Pinter script while the director was on location in Rome filming Eve (1962). (3)

However, like Michael Anderson, Losey found it near impossible to raise finance for the script of The Servant. It was eventually Leslie Grade, a talent agent with The Grade Organisation, who backed the film having made a tidy sum from two Cliff Richard films, and co-financed it with ABPC and the National Film Finance Corporation. Anderson was paid £12,000 for the rights but then other hurdles presented themselves.

Bogarde's partner and manager Tony Forward worried that the role of Hugo Barrett, the manservant to upper class Tony, would harm Bogarde's career as The Servant seemed to be just another 'completely homosexual picture' so soon after his breakthrough role as the closeted bi-sexual barrister Melville Farr in Basil Dearden's Victim (1961). (4) Bogarde, uneasy about the role, even suggested Ralph Richardson for Hugo Barrett but Losey informed him Richardson was too expensive and 'you'll have to do.' (5)

Pinter's script removed the single narrator of Maugham's melodramatic novella and 'its yellow book snobbery and the arguably anti-Semitic characterisation of Barrett - oiliness, heavy lids - replacing them with an economical language that implied rather than stated the slippage of power relations away from Tony towards Barrett'. (6) Both Losey and Bogarde later refuted the homosexual reading placed onto the film, one perhaps traced back to the strange incident between Maugham and his own servant that inspired the original novella, and preferred to see the relationship between Tony and Barrett as one defined by sadism and domination.

In terms of power relations, Pinter and Losey didn't exactly hit it off in an initial meeting when Losey presented the writer with notes to rewrite the script. After suggesting Losey should go and make another film, the director tore up the notes and they agreed to start again, from then on developing an intense collaborative working partnership where 'material from the script was rarely simply excised wholesale. Instead it was transposed, concentrated or dispersed'. (7) The original 1961 script was revised and the final version prepared by January 1963.

Ealing alumnus Norman Priggen, an assistant director on Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949) and The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) among others, was hired as co-producer and his relationship with Losey matured into a production partnership lasting over seven films. Designer Richard Macdonald, who had worked with Losey on The Sleeping Tiger and Eve, created the meticulous interiors of Tony's Chelsea house at Shepperton.

While the studio housed the claustrophobic amalgam of rooms built around a central staircase, exteriors were shot in Royal Avenue, with Tony's house opposite Somerset Maugham's former home, King's Road for the opening titles and our first view of Barrett outside Thomas Crapper's premises, and Chiswick House to stage Tony and his girlfriend Susan's weekend at the Mountsets' home.

Bogarde recommended the twenty-three-year-old James Fox to Losey for the role of Tony after seeing him in an ITV Play of the Week, 'The Door' (transmitted 20 May 1962), acting under the name of Oliver Fox. He phoned Losey to try and catch the rest of the play after Bogarde, later recalled, saw something in Fox: 'Under the grace and breeding, the golden-boy innocence, I sensed, and I don't for the life of me know why, a muted quality of corruptibility. This young man could spoil like peaches; he could be led to the abyss.' (8)

As Fox recalls in the DVD interview in this edition, it was a serendipitous route to casting the film. He was going out with Sarah Miles, whom Bogarde had already approached to play Barrett's 'sister' Vera in the film, and their agent was his father Robin Fox, who also happened to be Losey's agent. Miles and Fox met Bogarde at the premier of The L Shaped Room and she also suggested Fox for the part.

It was mutually agreed both Miles and Fox would be excellent casting but their relationship, already deteriorating, eventually caused Losey some problems on set. During the infamous scene of Vera's seduction of Tony on a leather chair, she branded Fox a 'great stinking queer' for wearing a combination of karate dressing-gown and fur boots for the scene. Her agent Robin Fox had words with her, Losey gave her an ultimatum and Fox completed the scene sans fur boots. (9)

Fox recalls a crude, silent screen test with Losey, paid for by the director, shot in a flat in Queen's Gate and writer Paul Mayersberg claimed Fox's inexperience generated many retakes until Losey found what he wanted and he and editor Reginald Mills then shaped the performance in the cutting room. Wendy Craig's casting as Susan, Tony's girlfriend, was again via Dirk Bogarde's suggestion after working with her on Basil Dearden's The Mind Benders (1963) but she was often regarded by Losey as the weakest link in the ensemble.

Shooting began on 28 January 1963 with celebrated British cinematographer Douglas Slocombe as a replacement for Losey's original preference of Christopher Challis. Slocombe, an Ealing veteran of, among others, It Always Rains on Sunday (1948), Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), The Man in the White Suit (1951), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), Mandy (1952)and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953) devised a four phase lighting scheme for the film to highlight the deterioration within the house.

The shoot was interrupted a fortnight later when Losey was incapacitated by pneumonia and, in his ten-day absence, he asked Bogarde and Richard Macdonald to continue shooting to his script specifications. On his return, wrapped in blankets and hot-water bottles, he directed from a bed and, apart from three scenes, reshot everything that Bogarde and Macdonald had filmed.

Mills efficiently produced a rough cut immediately after the end of filming on 19 March 1963, editing the film as it was being shot. Pinter was affronted by Mills's trimming back of his repetitive dialogue and he also sent a very angry letter to Mills after some rather condescending and disingenuous comments the editor made about him in an interview and told him succinctly 'to go and fuck yourself'. With post-production complete and a clean bill of health from the British Board of Film Censors (despite some minor concerns over Tony's seduction of Vera in the leather chair after a screening with John Trevelyan), Losey then struggled to get distributors interested in The Servant, which he proudly claimed was 'a remarkable film'. (10)

Even though it was one of three British films represented at the Venice Film Festival, it was considered unreleasable until Warner Brothers' European booker Arthur Abeles, left with a gap in his release schedules, found a home for it in the Warner Leicester Square where it aptly received its British premier on 14 November 1963 some five months after the climax of the Profumo scandal.

'...my soufflés have always received a great deal of praise in the past, sir'This searing film 'about the servility of our society, our age, the servility of the master, the servility of the servant and the servility of attitudes of all kinds of people in different classes' is dominated by Losey's precise control and staging. (11) A true collaboration with designer Richard Macdonald and cinematographer Douglas Slocombe, The Servant chronicles the slow disintegration of what to all intents and purposes is the sovereign state of Tony's house in Chelsea as it is invaded and transformed by outside forces. The slothful and indolent Tony (an impressive debut from James Fox), a symbol of upper class imperial decline, has acquired the house and interviews a potential manservant, Hugo Barrett (a stunningly brilliant Dirk Bogarde).

Barrett has an agenda, subtly revealed to begin with as he begins to tastefully decorate the house and minister to his master's needs. However, Tony's fiancée, Susan, detects an undercurrent in Barrett's relationship with Tony and a battle of wills ensues over who will have sovereign power - of Tony and of the house. Class and power are transmogrified, as Barrett's 'sister' Vera arrives to seduce Tony and allow Barrett's agenda to move into full gear.

A working class revolution takes place, the servant and the master swap places as power fragments and reforms and the bright white Chelsea house is filled with shadows, becomes a prison cell possessed by a demonic, corrupting force which prompts Tony's slide into a hell of Barrett's construction.

This devious plan is played out in the film as a series of distinct acts and where set decoration, lighting, the placing and use of objects, costume and music essentialise the transformation of a servant's deference into a domination over his master. Performance and dialogue also trace this release of, what Colin Gardner refers to as, Barrett's primal force that grows in power and influence during the film.

The film describes a web in which various couplings are caught, presenting an interchange of power and domination between Tony, Barrett, Susan and Vera. The house becomes a series of doorways into a labyrinth, one gradually diminishing and pushing the exterior world away. Losey continually places characters in doorways, emerging into or out of rooms to denote the shifting of power, providing a visual analog to the interior of the psyche, where all the characters peer into or out of rooms or are caught in reductive, distorting mirrors.

The film opens with the black figure of Barrett walking towards Royal Avenue, passing by the showroom of Thomas Crapper where Losey's camera lingers on the 'by appointment' coat of arms on the shop front before pulling back to reveal the name of said sanitary engineers and Barrett crossing the road outside. The sign of royal approval, of status, is contrasted with the figure of Barrett, who 'emerges from the primordial depths of the toilet, like some backed up excremental waste.' (12)

In a simple but witty sequence, he is already a representation of the filthy tide now about to wash up on the shores of Tony's indulgent respectability. Tony as an 'imperialist project' is also symbolised in the pipe dream of clearing the jungles of Brazil to build three cities where he'll be able to grant the peasants a new life. He refers to Barrett as a peasant towards the end of the film, long after his dream has failed and said peasant has revolted.

Barrett's first encounter with Tony, at the empty house, is equally a signifier of things to come. Losey holds on a shot of Barrett gazing up the central staircase. The staircase is a pivotal emblem of the battleground in the house, the shifting escalation of dominance and power and the rooms off it giving characters the power to reconfigure vertical and horizontal space. Barrett finds Tony asleep, a supine physical condition which Losey repeats throughout the film. Tony is rarely upright. He's either lying down or slouched in a chair. In the climax, he's crawling on his knees or slumped in a corner.

The three o'clock interview which assesses Barrett's suitability to be a manservant ('Well, my… my soufflés have always received a great deal of praise in the past, sir') also reveals Barrett to be not quite what he seems when he slips up in his distinction, pointed out by Tony of course, between Viscount or Lord Barr.

As Bogarde noted of the character's deception: 'Barrett's a liar... if you know what a gentleman's gentleman is like, you'll know Barrett could never have been one. I don't think he'd ever made a soufflé in his life.' (13) Even the workmen decorating the house can detect the mutton dressed as lamb as Barrett attempts to better himself to the detriment of these other working class figures.

Decor and taste are also markers in the field of battle. As designer Richard Macdonald recalled of the transformation of the house: 'at the beginning it is an empty shell, it's cold and has no personality; then it's suddenly painted and beautified; then it gradually rots; and then at the end it takes on a completely new personality, it's partially repainted, it has black ceilings and a gaudy, meretricious look in everything.' (14)

Barrett initially oversees a white and blue scheme for the house, filled with tasteful neo-classical objects and paintings. There is a tug of war between Susan and Barrett over who is the arbiter of taste and style in the house, over the installation of a 'proper spice shelf for the kitchen', the placing of flowers, objects and the removal of 'chintz frills'. Objects move around the house: the contents of Barrett's room upstairs creep into the drawing room downstairs as the decor becomes darker, satanic. Neoclassical vases and figures briefly materialise into alcoves, a reminder of the frozen in aspic poses of Lord and Lady Mountset we see during Tony and Susan's weekends away where class is determined not by the possession of a spice rack but by defining what a poncho is.

A muscled male bronze seems to signify a homoerotic, passive aggressive tension exuded by the two men and its position alters in the film from the top of a display cabinet to a sideboard. When Tony receives the gift of a karate style dressing-gown, Barrett glances back to look at it but might as well be gazing at the bronze positioned in between them judging by his adulation of 'it's very handsome, sir.'

A parallel to the bronze can also be seen in the muscle magazine pictures pinned to the wall of Vera's room and what look like sketches of male nudes in Tony's study. An early and witty indication of the manipulation of masculinity in the film can also be seen in Barrett's preparation of a bowl of hot water for Tony's feet. Not only does he infuse the water with the appropriately named 'Stag' salt but he also bows and scrapes, pulling off Tony's socks, as his master hurls a veiled insult at him, 'You're too skinny to be a nanny, Barrett.'

Underlining the various items of military paraphernalia - portraits, statues and cannons - which form the decor, there's also the double entendre in a later scene when Barrett, serving Tony some mulled claret, notes he was known in the army as 'Basher Barrett' because 'I was a very good driller.'

When Barrett has finally claimed Tony's soul at the end of the film, Tony fawns to him, 'I have a feeling we’ve always been buddies.Like the Army.' The ball games they play on the stairs, when deference has gone out of the window, also carry a sublimated homosexual charge, especially when Barrett complains of an injury received from the ball: 'I'm not staying here in a place where they just chuck balls in your face.'

Slowly, inexorably Barrett dominates, passing through the veneer of class and deference as easily as he slips through the doorway disguised as a bookcase that separates the drawing room, the space of privilege, from the kitchen, the engine of domesticity. His character continually shifts between these spaces.

Note his obsequious demeanour when Susan first comes to visit and mocks his pretensions as he serves wine while wearing white gloves ('Italian, miss. They're used in Italy' to which she replies, 'Who by?') and then, in direct contrast, observe his post-supper slump among the dirty dishes, picking his teeth, downing Guinness, blowing cigarette smoke and idly throwing the white gloves to one side as his gimlet eyes suggest a dark plan already being formulated.

The signature convex mirror, a reflection of the claustrophobia in the house, also first appears before the supper scene and is a symbol of Barrett's trap, where all the figures who enter the room are eventually crushed within its warped reflection. Other distortions and reflections occur: Barrett calling for Vera to be introduced to her master is shot through a huge brandy glass, military photographs surround Tony adjusting his tie in a mirror and Vera's seduction of Tony is caught in the shiny surfaces of kitchen appliances.

Cigarette smoke is another visual code in the film. Characters exhale great clouds of it as they contemplate their powerful deeds, many of them sexual, or their machinations in gaining superiority over one another. Vera seductively allows a glob of smoke to escape from her lips when Barrett gets familiar with her on the kitchen table, the first suggestion of the incest which will shock Tony and Susan later but which turns out to be another of Barrett's deceptions in the film.

It marks intimacy between Susan and Tony when we see them lying side by side in the drawing room, listening to the Cleo Laine title song. Their coupling is all too brief when Barrett oversteps the mark by disturbing them, confirming Susan's view of Barrett as a demonic entity, who appears at will like 'a Peeping Tom' or as Tony mocks, 'a vampire too on his Sundays off'. She resents his dominance and the rest of the film is a tug of war between them for the possession of Tony's soul. In the film's bleak conclusion, Barrett blows a huge cloud of cigarette smoke into Susan's face, to mark her defeat and humiliation in the scheme of things.

The central staircase records the progress of the war. Losey frames a shot of Barrett dusting the bookcase in the foreground and Susan peering down at him from the first floor as a prelude to the scene where she brings flowers into Tony's bedroom during a spell of illness. When Barrett tries to remove the flowers, and we see him in the mirror first as he enters the room, she simply barks 'put that down', reaffirming her exercise of power. However, in one of the film's great exchanges of dialogue, Barrett undercuts her as she leaves the house. 'I'm afraid it's not very encouraging, miss...' he pauses, '...the weather forecast'.

That very British sensibility of talking about the weather is married to a veiled insinuation about their ongoing stormy relationship it seems. As he closes the door, watch his self-satisfied smirk. It's Bogarde briefly and brilliantly revealing the man's satanic depths. She holds on to a lamppost outside, clearly troubled by the skirmish. Losey doubles this shot later, at the film's end, when in the final humiliation dealt by Barrett, she runs from the house and clings to a tree, sobbing.

'Vera, are you ready?'The cycle of domination and submission continues to be played out on the staircase throughout the film - Vera's infiltration of the upper echelons of the house spelling out Tony's demotion to submissive, love struck fool; the revealing shadow of Barrett on the landing as Susan and Tony return home to find him and Vera in their bed; the same shadows playing over the staircase during the passive aggressive ball games; the final triumph of Barrett as he runs his fingers up the bannister past a slouched, debauched Tony caught behind the prison bars of the staircase.

Vera's manipulation by Barrett, after he invites her to London, is reflected in Barrett's treatment of women in general. As he phones Vera, his forward planning underlined by a terse, 'Vera, are you ready?', he's assailed by an impatient woman outside the phone box. He first observes her legs but after she taps on the window with a coin, his hand slaps onto the glass and covers up her face. 'Are you being a good girl?' he asks Vera, clearly regarding the woman outside the phone box as the opposite, cancelling her assertiveness as a consequence of her being a 'bitch.'

Later, Vera herself is introduced with a close up of her legs as she and Barrett totter down the steps of St. Pancras. Losey brilliantly intercuts her arrival in London with a sequence between Susan and Tony set in a restaurant. Vera, wide-eyed at the sights of the big city and yet overly intimate in the way she holds onto Barrett's thighs in the taxi from the station, further suggesting an incestuousness to the 'brother-sister' relationship proposed at this stage, is given a blousy, seductive jazz theme by composer Johnny Dankworth.

As the instrument of Tony's destruction arrives, the restaurant hosts a series of intriguing variants on dominance and submission: bickering lesbians, a domineering bishop advising a younger cleric, a metropolitan couple. The down to earth Susan, trapped beneath the icy formality of the Mountsets and reluctant to sink into the hell occupied by Barrett and Vera, is reprimanded for judging Tony's choice to hire Barrett. Their relationship seems wounded at this point and, later, Vera's seduction of her man severely undermines it too.

Half way into the film, Barrett deploys his secret weapon to devastating effect, using Vera to reconfigure space wherein 'rooms that were once clearly demarcated as a haven or sanctuary are now the site of desecration and open trangression.' (15) The kitchen first presents working class sexual excess in an expression of short skirts, clouds of cigarette smoke and Barrett's sultry looks at Vera over a cup of tea. Vera then turns up in Tony's bathroom, undermining his casual misogyny of 'she is having a bath in my bathroom', and there follows a delicious scene where Barrett and Vera ape Tony's pretentiousness. 'I'm going to have a bath in his bathroom,' drawls Barrett as he briefly seizes control of Tony's inner sanctum, sits under a sun lamp and demands to be slathered in cologne.

Losey's control is at its finest in the moment when Vera finally gets her man Tony in the kitchen, under orders from an absent Barrett. They are accompanied to the pulse of a dripping tap and a ticking clock to signify Tony's dammed up, repressed sexual energy. 'In't it hot in here?' purrs Vera as she curls her legs up and sits on the kitchen table. The ticking clock is like a bomb about to go off and the spectre of Susan, a slowly receding representative of his pre-Barrett existence, is surely there in the unanswered telephone call as Tony advises Vera that her skirt is too short. Their lovemaking is reflected in the kitchen surfaces and the transgression is reinforced by Dankworth's sultry score.

'Did she manage to do anything for you, sir?' asks Barrett knowingly on his return and of the guilty looking Tony. Barrett reinforces guilt when Tony claims Vera was too under the weather to do the washing up and deliberately feigns mishearing, asking him 'Under the what, sir?' It's at this stage that Tony joins in the subterfuge, sending Barrett on a false errand for brown ale to not only give him time to get Vera out his room but to indulge in further sexual play. However, this time Losey specifically emphasises the trap and frames their embrace in the vortex-like convex mirror.

Following this is the seduction in the leather chair, a dominant and very masculine item of furniture which has already appeared several times in the film, and here bobs up and down to a ticking, chiming clock before Vera is enticed from her room by Tony to the strains of Laine's woozy, self-destructive and corrupting jazz number. At the same time, in a stunning reveal we see Barrett in her bed through the bars of the bannister as she descends the stairs.

Losey's shot of the stretched out, semi-naked couple in the chair is, of course, an analog to the iconic Christine Keeler photograph by Lewis Morley. The establishment-baiting image of her sitting naked with her legs enticingly spread around the back of the Arne Jacobsen chair to preserve her decency was taken at the height of the Profumo scandal, which had broken just as the film completed shooting.

Susan attempts once more to assert her status in the house, bossing Barrett around, rearranging furniture and flowers. It's like a tussle between a guardian angel and an impudent demon and one shot of Susan arranging the flowers, as Barrett reels from her insults, makes her look quite demonic as she demands, 'What do you want from this house?' He smirks at her and simply replies, 'I'm the servant, miss.' We know full well he's not just a servant, he's a revolutionary gradually knocking the foundations from under Tony's indolent sense of privilege.

Those foundations collapse completely when Tony and Susan find Barrett and Vera in their bed. Losey tangles together defiant shadows, the ever present staircase and the collapsing dimensions of the convex mirror wherein both couples are doubly reflected, doubly destroyed. The whiff of incest is dissipated, Tony's seduction by, and Barrett's relationship with, Vera is revealed. 'We shall have to tell our secret to Mr. Tony,' he concludes. This humiliation is compounded for Susan after Tony asks her to 'come to bed', to make love in the same bed still warm from Barrett and Vera's activities.

After dismissing the pair, Tony's world disintegrates and the house grows ever darker, unkempt and unloved. Tony sobs in Vera's bed beneath the wall plastered with muscle men pictures and we wonder just who it is he's missing - Vera or Barrett? Shortly after, a contrite Barrett spins his own sob story across the class divide in a pub, Losey's visuals demarcating Barrett's tale of mutual humiliation about Vera through partitions, bunches of flowers and beer pumps.

'She's living with a bookie in Wandsworth... Wandsworth!' he decries, the location clearly of more distress to him than her alleged infidelity. Losey is extremely clever here as the scene opens with the pub interior reflected in a mirror, is followed by a pan to Barrett in the foreground chatting to Tony and concludes with a reverse shot of the pub wherein the two men have swapped sides, a literal reversal of the relationship, a reversal of their status.

Barrett, with the upper hand, then employs his games to reduce Tony further. They bicker like a gay couple and Barrett reaffirms his dark origins in the criticism of all the 'muck and slime' surrounding him as he attempts to keep the now gloomy house in order and to make ends meet. Tony again lies supine on the couch, his dreams of creating cities in Brazil all but gone, as Barrett complains that 'butter's gone up tuppence a pound.' The decor changes (pointedly the spice rack is ripped off the wall), a more satanic atmosphere is generated, class warfare is in full flight ('I'm nobody's servant') and Barrett controls Tony through drink and drugs. Dankworth's music becomes more and more atonal and strained, echoing this nightmare.

The house is transformed into a baroque brothel, where orgies occur in an endless configuration of dark spaces reflected and refracted by mirrors, and Tony, when not deferring to Barrett or hiding from him in sheer terror, simply ends up crawling about his prison cell under the influence of 'something special from a little man in Jermyn Street' or viewing his world through a distorting crystal ball. The master-servant relationship is now based on a 'primordial, libidinally driven annihilation of sexual and class difference.' (16)

Vera returns, looking for money so she can go into hospital (suggesting a pregnancy perhaps), but this is yet another subterfuge. As Barrett seemingly kicks her out into the rain, Losey shows him smirking at Vera and shouting in mock indignation for Tony's benefit, 'get back to yer ponce'. He then shields her on the doorstep, hiding their conversation or furtively kissing her behind the front door. Vera reappears in the climax of the film, in the centre of the web, as Susan makes one final attempt to shock Tony back into reality, her trauma accompanied by the now nightmarish strings and discordant sax backing Cleo Laine's forlorn song.

Slocombe's lighting is high contrast, full of shadows and renders the end of the film intense, desolate and surreal and, while it may seem to be a triumph for Barrett as he climbs the stairs to the top of the house and runs his fingers along the bannister, you are left questioning what kind of revolution this is - if indeed it is about sweeping away the remains of privilege and class snobbery. The house becomes an hermetically sealed world where 'we are left with a sense of inertia rather than a promise of progress' and one symbolised by the stopped clock that Slocombe's camera closes in on just as the screen fades to black. (17)

(1) David Caute, Joseph Losey - A Revenge on Life

(2) John Coldstream, Dirk Bogarde - The Authorised Biography

(3) Ibid

(4) Ibid

(5) David Caute, Joseph Losey - A Revenge on Life

(6) Nick James, Joseph Losey & Harold Pinter: In search of poshlust times, Sight and Sound, June 2009

(7) Amy Sargeant, The Servant, BFI Film Classics

(8) John Coldstream, Dirk Bogarde - The Authorised Biography

(9) David Caute, Joseph Losey - A Revenge on Life

(10) Ibid

(11) Colin Gardner, British Film Directors - Joseph Losey

(12) Ibid

(13) Ibid

(14) Amy Sargeant, The Servant, BFI Film Classics

(15) Colin Gardner, British Film Directors - Joseph Losey

(16) Ibid

(17) Amy Sargeant, The Servant, BFI Film Classics

About the transfer

This is a very clean, sharp 1.66:1 restoration and is wonderfully detailed. Clothes, faces and objects look crisp and clear. Appropriate film grain is present and the contrast levels are layered in crisp whites, steel greys and deep black. The location sequences in the snow shine brilliantly in juxtaposition to the gradual darkening of the house interiors. Douglas Slocombe's exquisite, award-winning black and white photography is very well served by this truly handsome looking high definition picture. The mono soundtrack reproduces dialogue clearly and Johnny Dankworth's jazz score is well represented and there are no pops, crackles or warbles. This is altogether gorgeous.

Special features

James Fox interviewed by Richard Ayoade (45:26)

Director and actor Ayoade discusses the making of The Servant with actor James Fox, who played Tony. Various elements serendipitously came together as the film was cast. Bogarde apparently saw Fox on television and advised Joseph Losey of his potential for the role of Tony, and agent Robin Fox represented both Sarah Miles and James. Ayoade sometimes loses his thread in his questioning but he does pick up on some of the precision that Losey brought to shooting on the set and many of the themes about power and control in the film. Fox is a delight and his stories about his screen test are amusing and offer an insight into Losey's process and character.

Interview with Wendy Craig (5:26)

Craig chats about the British films of the 1960s and her reaction to the script. She believes the character of Susan is rather underestimated, contemplates the power struggle she has with Bogarde's character Barrett and her concerns about Fox's inexperience. Losey 'took his work very seriously' and she was apparently told off for handing out sweets to the cast and crew.

Interview with Sarah Miles (10:18)

She apparently demanded of her agent Robin Fox that she wouldn't play Vera without her then boyfriend (and Robin's son) James Fox in the cast. She was close to Losey and she explains that he allowed actors freedom because he wanted to concentrate on the atmosphere of the film and yet Miles and the rest of the team were very aware they were working on something quite special. She is particularly funny about inverted snobbery in the acting profession and her hotel calamity on the New York promotional tour for the film.

Interview with Stephen Wooley (10:34)

The director and producer recalls the BBC television showing of The Servant when he was a teenager and saw it as part of his introduction to world cinema. Believing it to be a 'truly odd film', he comments on the casting of Bogarde, his first encounter with Pinter, the black and white cinematography, the impact of the Vera and Tony seduction scene and the film's implications for class distinction. As an interview it's a tad dry.

Harry Burton on Harold Pinter (13:02)

Burton is the director of Channel 4's excellent documentary 'Working with Pinter' and here provides biographical detail about Pinter and his journey from actor to screenwriter, eventually dropping out of RADA to study the microcosm of people's lives in his writing. Burton explains that Pinter was very interested in the politics of class and privilege and had a political consciousness from his earliest days that fed into the highly charged The Servant and its challenge to the status quo. An absorbing if brief bit of context about the intense collaboration between Pinter and the leftist Losey that had its roots in the television screening of Pinter's 'A Night Out', about his screenplay and his appearance in the film.

Bogarde biographer John Coldstream on Dirk Bogarde(18:37)

'The most enigmatic and complicated person I've ever come across', offers Coldstream of Bogarde. He describes Bogarde as a difficult but charming man with whom he spent four years assembling a biography and book of letters. He was always a reliable friend if you were in trouble and was always on the look out for stimulating projects and he found a perfect collaborator in Losey who went on to change his career. Coldstream's analysis of Bogarde's key films is fascinating and he sees The Servant as the step into 'art cinema' that Bogarde wanted to achieve and Losey and Borgarde as 'European' rather than natives of their own countries. In a very rewarding interview, he also covers the origin of the Pinter script, its journey to Bogarde and Losey, the uneasy first meeting between all three and Bogarde's standing in for an ill Losey for the first week of shooting and, finally, Bogarde's account of 'creating' Barratt from his biography 'Snakes and Ladders'.

Audio Interview with Douglas Slocombe (19:18)

A splendid Matthew Sweet interview with legendary cinematographer Slocombe at home in October 2012. This discusses the 'chamber drama' of The Servant and Losey's fascination for the class system in Britain, Slocombe matching between the exterior shoot at a house in Chelsea and the interiors completed at Shepperton. The sets also allowed him some flexibility for manipulated light and shadow during the shoot, particularly for the now iconic scene of Tony and Susan watching Barratt's silhouette on the staircase and Sweet also picks out the distorting effect of the mirror as another visual key to the film. Slocombe discusses working with Bogarde, Fox, Miles and Craig and how the performances worked in tandem with Losey's intentions for the film's mise-

Joseph Losey and Adolfas Mekas at the New York Film Festival 1963 (27:58)

A very welcome piece of archive dredged up from a US television series called Camera Three featuring the festival organisers, Losey and fellow director Mekas, who had brought Hallelujah the Hills to the festival, in conversation. They begin with a discussion about the importance of film festivals and then after clips from The Servant, Losey is interviewed about the film. He's asked about the 'existence of evil' and the sado-masochistic and homosexual overtones in the film as well as its tragedy of class and privilege. The discussion switches to the visual power of the film and Pinter's minimalist script. A fascinating record of the film's initial reception and Losey's view of cinema.

Tempo (30:20)

An archive edition of the ABC arts show Tempo entitled 'Harold Pinter Playwright', transmitted on ITV 3 October 1965 and narrated by John Kershaw. Produced by director Mike Hodges, this examines the nature of Pinter's work as it focuses on sudden intrusions and threats to security, the foibles and faults of people and his ideas about which Pinter claims it's merely a 'job of work' to put the material together for plays that dictate their own destiny. It's an 'activity that he can't explain' and he 'just writes'. He's also obsessed by the order and rhythm of writing and how exciting and funny it is working with words. This interview is interspersed with clips, documentary footage and photographs and Kershaw delves into Pinter's background, education, encounters with anti-Semitism in Hackney, his status as a conscientious objector and his early acting career. A wonderful summation of his early work and there are great clips from the 1965 Peter Hall production of The Homecoming featuring Paul Rogers, Ian Holm, John Normington, Terence Rigby, Vivien Merchant and Michael Bryant.

Joseph Losey talks about The Servant (5:41)

Brief archive interview with Losey about the subject matter of The Servant, the casting and censorship of the film.

Stills gallery

Great set of behind the scene stills of Losey at work with the actors and a number of atmospheric portraits.

Trailer (2:38)

Stylish trailer from 1963 that uses Barrett's dialogue to Tony in the pub and Dankworth's theme song over a series of black and white stills and clips.

The Servant

Springbok Productions - Associated British Picture Corporation 1963

StudioCanal Blu Ray / Released 8 April 2013 / OPTBD0763 / Cert 15 / 115 minutes / Black and white

BD Specs: Region B / Feature Aspect Ratio: 1.66:1 / Feature Audio: DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 / Video Codec: MPEG-4 AVC / BD50 / 1080P / English Language / English, French and German subs